Reserve Bank Organization Committee

April 1914

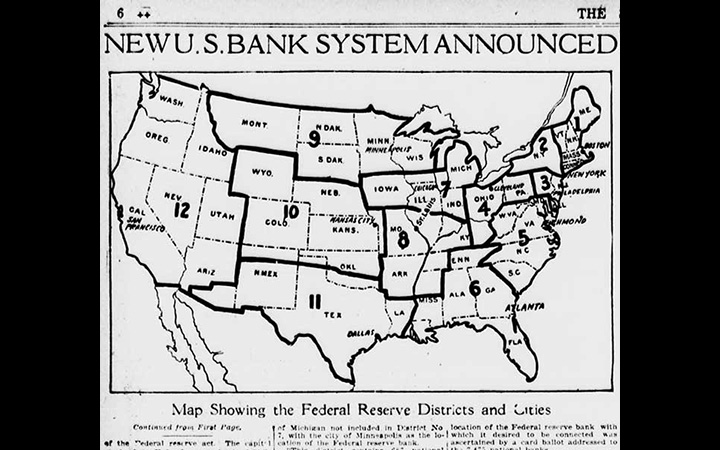

The signing of the Federal Reserve Act on December 23, 1913, created the Federal Reserve System, but now the institution needed to take shape. The Act established a Reserve Bank Organization Committee (RBOC) to select locations for Reserve Banks and draw district boundaries.

The RBOC comprised Secretary of the Treasury William G. McAdoo, Secretary of Agriculture David F. Houston, and Comptroller of the Currency John Skelton Williams. The RBOC was charged with designating between eight and twelve cities as Federal Reserve cities and apportioning the country into districts, each of which would contain one Reserve Bank city. Furthermore, the boundaries of each district had to take into account that region's "convenience and customary course of business" (Federal Reserve Act 1913).

RBOC members spent six weeks traveling 10,000 miles to allow business leaders, bankers, chambers of commerce, clearing house associations, and other representatives to make a case for why a Federal Reserve Bank should be located in their city. Public hearings were held in eighteen cities: Atlanta, Austin, Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Denver, El Paso, Kansas City, Lincoln, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York, Portland, St. Louis, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, DC. The hearings generated more than 5,000 pages of testimony and covered a wide range of topics, including testimony on banking conditions and commercial, industrial, and agricultural statistics. Representatives also discussed location, trade, transportation and communication links, and population growth.

In addition to holding hearings and accepting petitions from bankers and other parties, the RBOC polled national banks on their first, second, and third choices for Reserve Bank cities.

Some cities were obvious choices, such as New York, Chicago, and St. Louis, which were designated central reserve cities under the National Banking Act of 1863 and subsequent legislation. Despite the RBOC's efforts to clarify the criteria used to draw district lines and select Reserve Bank cities, several cities nevertheless sparked controversies over the eventual decisions.

The number of districts was already a heated issue that spilled over from earlier debates about the appropriate structure and governance of the System and the number of Reserve Banks. Those favoring a concentrated system felt that the number of Reserve Banks should be kept at a minimum and some, including financier J.P Morgan, thought that New York should have the largest Reserve Bank in terms of capital and should serve most of the northeastern United States. Bankers in other parts of the country thought otherwise, advocating for the maximum number of Reserve Banks with roughly equal capital to regionalize the system.

The Federal Reserve Act mandated that each Reserve Bank have a minimum capital of $4 million. Member banks had to subscribe an amount equal to 6 percent of their own capital and surplus in their Reserve Bank. To divide available capital more evenly across the districts, districts in the Northeast, with its higher concentration of commercial banks and bank capital, would necessarily be smaller geographically than districts elsewhere. The availability of bank capital, however, was just one of many factors behind drawing the districts.

On April 2, 1914, the RBOC announced its decision and published a report describing the selection process. In drawing the districts and selecting Reserve Bank cities, the committee considered the following criteria:

- "The ability of the member banks within the district to provide the minimum capital of $4,000,000 required for the Federal Reserve Bank, on the basis of six per cent of the capital stock and surplus of member banks within the district."

- "The mercantile, industrial, and financial connections existing in each district and the relations between the various portions of the district and the city selected for the location of the Federal Reserve Bank."

- "The probable ability of the Federal Reserve Bank in each district, after organization and after the provisions of the Federal Reserve Act shall have gone into effect, to meet the legitimate demands of business, whether normal or abnormal, in accordance with the spirit and provisions of the Federal Reserve Act."

- "The fair and equitable division of the available capital for the Federal Reserve banks among the districts created."

- "The general geographical situation of the district, transportation lines, and the facilities for speedy communication between the Federal Reserve Bank and all portions of the district."

- "The population, area, and prevalent business activities of the district, whether agricultural, manufacturing, mining, or commercial, its record of growth and development in the past and its prospects for the future."

Of the thirty-seven cities that applied to have Reserve Banks, these twelve were selected: Boston (District 1), New York (District 2), Philadelphia (District 3), Cleveland (District 4), Richmond (District 5), Atlanta (District 6), Chicago (District 7), St. Louis (District 8), Minneapolis (District 9), Kansas City (District 10), Dallas (District 11), and San Francisco (District 12).

New Orleans and Baltimore were in an uproar when the decision was announced, as both cities were larger than some selected. Large protests were held, and some of the cities' political leaders denounced the RBOC's decision.

Richmond's selection as a Reserve Bank location also engendered criticism, because Atlanta—another southeastern city—was also designated a Reserve Bank city. Some, like Henry Parker Willis, who aided the RBOC in the organization of the Federal Reserve System, argued that political pressure played a role in Richmond's selection. Others suspected political pressures, and ties to President Wilson's cabinet, in Cleveland's selection over Cincinnati or Pittsburgh. Some questioned why there were two Reserve Banks in Missouri—Kansas City and St. Louis—and linked the decision to the numerous Missouri politicians then in office.

As a result of the criticism that the RBOC received from both the public and Congress, it published a statement defending its decision on April 10, 1914, and the results of the poll conducted among national banks. The RBOC explained that New Orleans didn't receive Reserve Bank designation because although the size of the banks in New Orleans, Atlanta, and Dallas were similar at the time, the previous decade had seen the Atlanta and Dallas banking markets double, while the size of the New Orleans market had changed little. As for Richmond, the RBOC referred to the bankers' poll that showed Richmond receiving more votes than Baltimore.

Bibliography

Federal Reserve Act, 1913. Pub. L. 63-43, ch. 6, 38 Stat. 251 (1913). Available on FRASER.

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. "Dr. Econ: First, why haven't the boundaries of the 12 Federal Reserve Districts been adjusted to reflect changes in population or economic growth? Second, do the western states receive similar central banking and research services from the Federal Reserve, as do other areas of the country where Reserve Banks serve smaller geographic areas or populations?" May 1, 2001.

Hammes, David, "Locating Federal Reserve Districts and Headquarters Cities," Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, The Region, September 1, 2001.

Houston, David F. Eight Years with Wilson's Cabinet, 1913 to 1920: With a Personal Estimate of the President, Volume 1. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Co, 1926.

Johnson, Roger T. Historical Beginnings...The Federal Reserve. Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, revised February 2010. Available on FRASER.

New York Times. "Commanding Bank Most Needed Here," January 7, 1914.

Primm, James Neal. A Foregone Conclusion: The Founding of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 1989. Available on FRASER.

Reserve Bank Organization Committee. "Decision of the Reserve Bank Organization Committee Determining the Federal Reserve Districts and the Location of Federal Reserve Banks under the Federal Reserve Act Approved December 23, 1913." April 2, 1914, Available on FRASER.

Reserve Bank Organization Committee. "First-Choice Vote for Reserve-Bank Cities," 1914. Available on FRASER.

Reserve Bank Organization Committee. "Hearings before the Reserve Bank Organization Committee—New York, New York," January 1914. Available on FRASER.

Reserve Bank Organization Committee. "Location of the Reserve Districts in the United States," 1914. Available on FRASER.

Todd, Tim, "Drawing the Federal Reserve Districts," Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, TEN, Summer 2005.

Written as of November 22, 2013. See disclaimer and update policy.

X

X  facebook

facebook

email

email