Reserve Banks Open for Business

November 1914

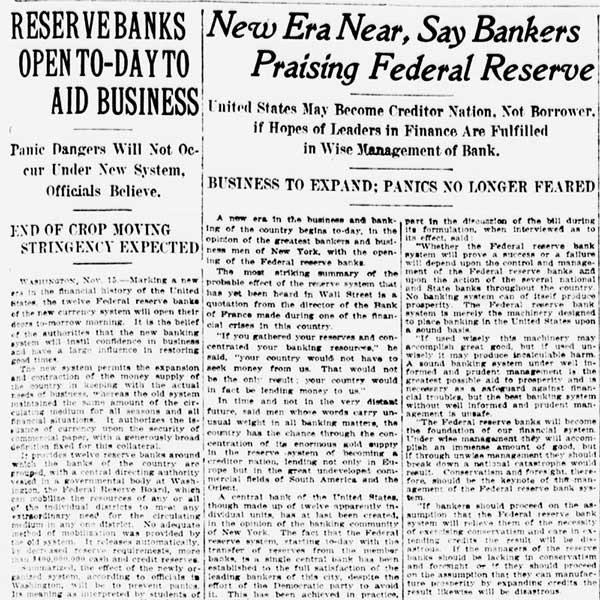

"The opening of these banks marks a new era in the history of business and finance in this country. It is believed that they will put an end to the annual anxiety from which the country has suffered for the past generation about insufficient money and credit to move the crops each year, and will give such stability to the banking business that the extreme fluctuations in interest rates and available credits which have characterized banking in the past will be destroyed permanently."– Treasury Secretary William McAdoo's Press Announcement

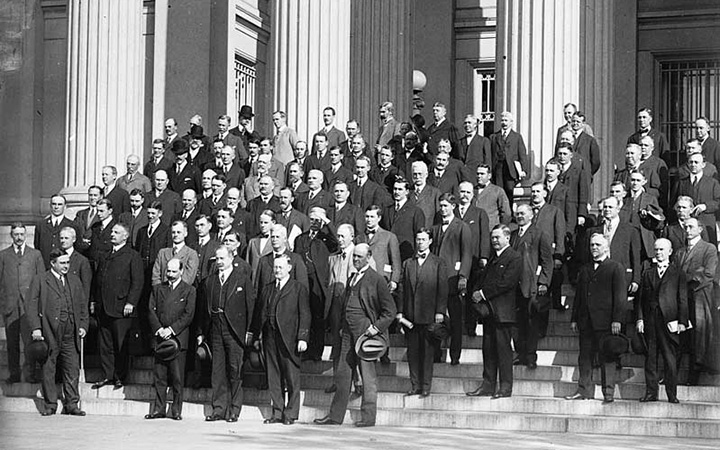

Some seven months after the Reserve Bank Organization Committee announced which cities and districts were selected, all twelve Reserve Banks opened on the same day, Monday, November 16, 1914. There was a sense of urgency to open the Reserve Banks, as World War I was affecting commerce and banking, but there were many organizational hurdles to overcome.

The first organizational challenge was to select members for the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, DC, and boards of directors for each of the twelve Reserve Banks. Under the Federal Reserve Act, five of the seven members of the Board were appointed by President Woodrow Wilson and confirmed by the Senate. Treasury Secretary William McAdoo and Comptroller of the Currency John Skelton Williams were automatically ex officio members. President Wilson appointed Wall Street financier Paul M. Warburg, economics professor Adolph C. Miller, Boston attorney Charles S.Hamlin, railroad executive Frederic A. Delano, and Birmingham banker W.P.G. Harding to the Federal Reserve Board. Hamlin served as governor (the counterpart to today's chairman), and the Federal Reserve Board took over the task of organizing and chartering the Reserve Banks.

The Reserve Banks answered to both the Federal Reserve Board in Washington and to a local board of directors. The Federal Reserve Board had authority over certain activities of the Reserve Banks, but, in general, the Reserve Banks had considerable independence in their day-to-day operations. The Banking Act of 1935 subsequently gave the Federal Reserve Board more authority over the Reserve Banks.

As is true today, the board of directors of each Reserve Bank was composed of nine members. Three are appointed by the Federal Reserve Board (Class C directors), and six are elected by the Reserve Bank's member banks—three bankers (Class A directors) and three others who are not bankers and represent commerce, agriculture, or an industry of the district (Class B directors). The chairman and vice chairman are chosen from among the Class C directors. From the Fed's inception through 1935, the chairman both presided over Reserve Bank board meetings, and, in his role as Federal Reserve agent, was the Federal Reserve Board's representative in the Reserve Bank.

The Federal Reserve Act specified that each Reserve Bank would have a governor to oversee the day-to-day operations of the Bank (the Banking Act of 1935 changed the titles of chief executive officers of Federal Reserve Banks to president). The Reserve Banks were also staffed with bankers; clerks, including a cashier, an auditor, a bookkeeper, a credit manager, and a discount clerk; some currency handlers; as well as support staff, such as stenographers and messengers. On opening day, some Reserve Banks had as few as eight employees (Minneapolis), though most had around twenty. The largest Reserve Banks, located in Chicago and New York, had forty-one and eighty-five employees, respectively, on opening day.

Organizing, staffing, furnishing office equipment, and even finding a building to operate out of had to happen very quickly for most Reserve Banks in order to open on November 16, 1914. In Atlanta, the bank's first location was chosen just sixteen days before opening. Some districts had to arrange temporary offices in established banks, as in Minneapolis, where Reserve Bank staff first operated out of the board room and teller cages of the Minnesota Loan & Trust Company. Treasury Secretary McAdoo instructed the Reserve Banks, "Buy a few chairs and pine-top tables. Hire some clerks and stenographers, paint "Federal Reserve Bank" on your office door and open up. The way to begin is to begin. When you make a start, everything will be smoothed out by practice."

Despite those modest beginnings, the Federal Reserve System was in place and operating. From then on, as McAdoo suggested, the Federal Reserve would learn and adapt in order to serve its purpose of creating stability in the financial system and the economy.

Bibliography

Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. "Chicago Fed History 1907-1914." Accessed September 20, 2013.

"Historical Overview: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis." Accessed September 20, 2013.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York."The Founding of the Fed." Accessed September 20, 2013.

Federal Reserve Board. "Press Announcement of Opening." November 15, 1914. Records of the Federal Reserve System, Record Group 82, Box 659, National Archives and Records Administration.

Fisher, Richard. "Vignettes of Dallas Fed History on the Eve of Our Centennial." Remarks before the Dallas Historical Society, Dallas, Texas, June 26, 2012.

Gamble, Richard. A History: The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta 1914- 1989. Atlanta: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, 1989.

Johnson, Roger T. Historical Beginnings...The Federal Reserve. Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, revised February 2010.

Written as of November 22, 2013. See disclaimer and update policy.

X

X  facebook

facebook

email

email