Redlining

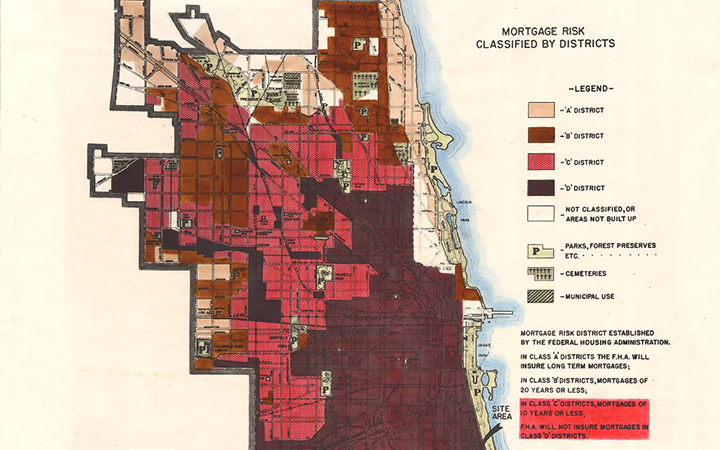

Redlining is the practice of denying people access to credit because of where they live, even if they are personally qualified for loans. Historically, mortgage lenders once widely redlined core urban neighborhoods and Black-populated neighborhoods in particular. The 1968 Fair Housing Act outlawed racially motivated redlining and tasked federal financial regulators, including the Federal Reserve, with enforcement.1

Redlining Practices before 1968

The federal government played a key role in institutionalizing and encouraging redlining through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The FHA was the architect of federally sponsored redlining from 1934 until the 1960s. Other federal agencies, such as the Federal Reserve, regulated the banks and thrifts that originated or bought FHA-insured loans. Of the interactions between the Federal Reserve and the FHA, not much has been written. Fed Chair Marriner Eccles was intimately involved in drafting the legislation that created the FHA but left little record of his views about the FHA's redlining practices. One biographer of Eccles concludes that redlining was "one major failing of the FHA that Eccles, and very few others at the time, even bothered to mention."2

The FHA was tasked with insuring "economically sound" loans, as part of an overhaul of the system of residential mortgage finance that had been decimated by the Depression. The FHA began redlining at the very beginning of its operations in 1934, as FHA staff concluded that no loan could be economically sound if the property was located in a neighborhood that was or could become populated by Black people, as property values might decline over the life of the 15- to 20-year loans they were attempting to standardize. For example, the FHA's 1938 Underwriting Manual emphasized the negative impact of "infiltration of inharmonious racial groups" on credit risk. To limit that risk, it recommended restrictive covenants that prohibit "the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended," which had become increasingly common in the 1920s. For the next few decades, the FHA generally favored loans on new construction in suburban areas rather than urban areas with older housing stocks or Black residents.3

Prior to the creation of the FHA, many banks were highly restricted in the amount of mortgage loans they were allowed to make.4 Mortgage loans were historically considered risky by those who had crafted federal banking law. Regulators such as the Federal Reserve feared that banks could be unable to pay depositors on demand if their funds were locked up in mortgages, especially since the secondary market for mortgages was limited historically. The advent of FHA insurance in the 1930s led to new federal bank regulations that encouraged banks to hold FHA-insured loans. FHA-insured loans were viewed as relatively safe given the federal insurance and because the uniform nature of FHA-insured loans supported a secondary market that made the loans relatively easy to sell if needed. As a result, banks originated roughly half of the mortgages insured by the Federal Housing Administration from 1935 to 1941.5

Federal policy reflected segregation in American society at large. While the FHA institutionalized redlining, the practice did not originate with the federal government, and public and private redlining were fundamentally intertwined.6

Redressing Redlining after 1968

The Fair Housing Act in 1968 banned discrimination in real estate and mortgage lending, including racially motivated redlining. Following the act's passage, the Federal Reserve and other regulators took a series of steps toward implementing the Act's provisions directed at discrimination in real estate lending. By 1971, the Federal Reserve's efforts included training for bank examiners and requiring the banks that it regulated to post Equal Housing Lender information in its lobbies.7

The Federal Reserve improved these functions over time as it took steps to identify shortcomings and in response to feedback. For example, the Board of Governors hired a consultant who, in 1978, issued a report describing "mild hostility" by examiners to civil rights compliance and "hesitance" by the Board to unambiguously commit itself to vigorously enforce or prioritize civil rights laws.8 In response, in the late 1970s, the Board determined that this enforcement was not sufficiently comprehensive or forceful and strengthened it in several ways. The Board created a specialized enforcement program, a formal process to promptly respond to complaints, and several other measures.9 Both the Board and Reserve Banks also added staff specializing in civil rights.

Meanwhile, community groups continued to assemble evidence that lenders remained engaged in redlining, in part based on data made available through the 1974 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. In 1977, Congress passed the Community Reinvestment Act to affirm the obligation of federally regulated financial institutions, such as banks, to reinvest in the low- and moderate-income communities where they operate, consistent with safe and sound operation. Altogether, these reforms helped end redlining as a widespread legal practice, even as community groups continued to protest lingering financial inclusion issues.

Community groups also pushed the Board to use their available powers. One flash point came in 1975 when the Board dismissed concerns that Marine Midland bank was not serving the convenience and needs of the communities where its banks were based. The Board resisted using its authority under the Bank Holding Company Act (BHCA) to "achieve favored social objectives."10 Two years later when the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was under consideration, Arthur Burns would testify that the Fed already had the authority it needed under the BHCA to consider whether banks were meeting the credit needs of their communities. The passage of the CRA in 1977 prompted the Fed to change its approach. Under the CRA, federal agencies encourage lenders to help meet local credit needs in a manner consistent with safe and sound operation, and assess lenders' records of doing so. To facilitate compliance of lenders with the CRA, the Federal Reserve established its community development function in the early 1980s. Since then, this function has evolved to promote the economic development of low- and moderate-income communities by studying what works and sharing practice-informed research with lenders and community groups.

Today, Federal Reserve policy continues to be informed by the long lasting legacy of public and private redlining. The Federal Reserve has referred several instances of redlining to law enforcement and continues to enforce fair lending laws.11 Chair Powell has described the Fed's robust supervisory approach as "critical to addressing racial discrimination."12 In 2022, federal banking regulators issued a notice of proposed rulemaking to amend the implementation of the CRA to ensure that the law is effective in supporting a robust and inclusive financial services industry.

Endnotes

- 1In enforcing fair lending laws, the Federal Reserve Board defines redlining as "a form of illegal disparate treatment whereby a lender provides unequal access to credit, or unequal terms of credit, because of the race, color, national origin, or other prohibited characteristic(s) of the residents of the area in which the credit seeker resides or will reside or in which the residential property to be mortgaged is located."

- 2 Mark Wayne Nelson. Jumping the Abyss: Marriner S. Eccles and the New Deal, 1933–1940. University of Utah Press, 2015: 171.

- 3 Price Fishback, Jonathan Rose, Kenneth A. Snowden, and Thomas Storrs. "New evidence on redlining by federal housing programs in the 1930s." Journal of Urban Economics, 2022.

- 4 Carl Behrens. Commercial Bank Activities in Mortgage Finance. National Bureau of Economic Research, 1952: 15-25.

- 5 Federal Housing Administration. Ninth Annual Report, 1942.

- 6 LaDale Winling and Todd Michney. "The Roots of Redlining: Academic, Governmental, and Professional Networks in the Making of the New Deal Lending Regime," Journal of American History 108, no. 1, June 2021: 42–69

- 7 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Fifty-eighth Annual Report, 1971.

- 8 Warren L. Dennis. Testimony. Banking Regulatory Agencies' Enforcement of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act and the Fair Housing Act: Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, US House of Representatives, 95th Congress, 2d Session, September 12, 14, and 15, 1978.

- 9 Nancy H. Teeters. Statement before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, US Senate, December 21, 1979.

- 10 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bulletin, December 1975: 893.

- 11 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. "Highlights of current issues in Federal Reserve Board consumer compliance supervision,"Consumer Compliance Supervision Bulletin, July 2018.&

- 12 Jerome Powell. "Community Development."Speech at the "2021 Just Economy Conference" sponsored by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, Washington, DC, May 3, 2021.

Published June 2, 2023. Jonathan Rose contributed to this article. Please cite this essay as: Federal Reserve History. "Redlining." June 2, 2023. See disclaimer and update policy.