Liberty Bonds

April 1917-September 1918

"Any great war must necessarily be a popular movement. It is a kind of crusade; and like all crusades, it sweeps along on a powerful stream of romanticism."

–William Gibbs McAdoo

World War I began in Europe in 1914, the same year the Federal Reserve System was established. During the three years it took for the United States to enter the conflict, the Fed had completed its organization and was in a position to play a key role in the war effort. Wars are expensive and, like every governmental effort, they have to be financed through some combination of taxation, borrowing, and the expedience of printing money. For this war, the federal government relied on a mix of one-third new taxes and two-thirds borrowing from the general population. Very little new money was created. The borrowing effort was called the "Liberty Loan" and was made operational through the sale of Liberty Bonds. These securities were issued by the Treasury, but the Federal Reserve and its member banks conducted the bond sales.

Generally speaking, the secretary of the Treasury proposes a funding plan for war financing and works with Congress to enact the necessary legislation, while the Federal Reserve operates with considerable independence from both the executive and legislative branches of government. But World War I was different. The Treasury and the Fed, united under one leader, worked together in both the creation of the financial war plan and its execution.

In the congressional debates over the structure of the Federal Reserve, the makeup of the Federal Reserve Board and even its very existence were key issues. The chair of the House Banking and Currency Committee, Rep. Carter Glass, opposed the idea of a central coordinating board. President Woodrow Wilson, however, insisted on a public agency with supervisory powers over the banks. The resulting compromise created a seven-member Federal Reserve Board seated in Washington, DC, with the secretary of Treasury designated ex officio as chair.1 The other members were the comptroller of the currency and five members appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Wilson's secretary of the Treasury, William Gibbs McAdoo, designed and arranged that compromise, and he emerged from the deal in charge of both the Treasury and the Federal Reserve. Congress cleared the bill in December 1913.2

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, it became immediately evident that an unprecedented effort would be required to divert the nation's industrial capacity away from meeting consumer demand and toward fulfilling the needs of the military. At the time of the congressional declaration of war, the American economy was operating at full capacity, so the requirements of the war effort could not be met by putting underutilized resources to work. The wartime population would have to sacrifice to pay the bill, and McAdoo understood the point. Shortly after war had been declared, he delivered a speech that he later recorded for posterity:

"We must be willing to give up something of personal convenience, something of personal comfort, something of our treasure—all, if necessary, and our lives in the bargain, to support our noble sons who go out to die for us."

But the question remained: how would the shift in output be arranged? How should the war be paid for? There were three possibilities: taxation, borrowing, and printing money.

For McAdoo, printing money was off the table. The experience with issuing "greenbacks" during the Civil War suggested that fiat money would generate inflation, which he thought would lower morale and damage the reputation of the newly issued paper currency, the Federal Reserve Note. McAdoo also opposed printing money because it would hide the costs of war rather than keeping the public engaged and committed. "Any great war must necessarily be a popular movement," he thought, "...a kind of crusade."

McAdoo chose a mix of taxation and the sale of war bonds. The original idea was to finance the war with an equal division between taxation and borrowing. Taxation would work directly and transparently to reduce consumption. Taxes are compulsory, and those who must pay are left with less purchasing power. Their expenditures will fall, freeing productive resources (labor, machines, factories, and raw materials) to be employed in support of the war. Another advantage of taxation was that Congress could set the rate schedule to target those they thought should bear the greatest burden. President Wilson and the Democrats in Congress insisted on a sharply progressive schedule—taxing those with very high incomes at higher rates than the middle class and exempting the poor. The highest marginal rate eventually reached 77 percent on incomes over $1 million.3

Some of the prominent economists of the day suggested that the war should be paid for entirely through such taxes, but McAdoo disagreed on grounds that the eventual cost of war was unknown at the outset. If the tax generated less money than was required, rates would have to be raised again and perhaps repeatedly. Furthermore, changing tax schedules always requires a controversial, complex, and drawn-out political debate. Indeed, as the estimated cost of the war effort escalated, McAdoo came to the conclusion that, despite the high rates, tax revenues would not cover anything like one-half the cost. Given the commitment to the progressive structure of rates, taxation had reached its acceptable limit. The revised goal was one-third from taxes and two-thirds from borrowing.

Financing a war by borrowing need not be inflationary if the public diverts income away from consumption to purchase bonds. Higher saving as a share of income would necessarily mean lower consumption. Such a change in saving behavior, however, would be difficult to engineer and far from certain. A high rate of return on the war bonds would be unlikely to work. High rates might tempt some to take momentary advantage and save more. But there is also an opposite effect. With high interest rates, a household's wealth would accumulate more rapidly. With that mechanism working on behalf of the saver, less saving from current income would be required to ultimately reach a target level of wealth. The two opposite tendencies would tend to cancel each other. Another problem with offering a high interest rate on the war bonds is that it might divert funding away from investments in physical capital when the war effort warranted an increase in productive capacity.

It is unclear if McAdoo understood that offering high rates of interest would not work. In any case, he was opposed to high rates because that would be a sign of weakness and would reward the rich—the very group the income tax was designed to target. He chose to keep the interest rates competitive with the current return on comparable assets. To many observers, a massive bond sale on these terms seemed to be an imprudent gamble. The worry expressed by bankers and bond dealers at the time was unanimous: the bonds might not sell without the promise of an extra-attractive return. Moreover, the critics pointed out, only a few Americans had any direct knowledge about bonds, and fewer still actually owned any.

It was at this point that McAdoo conceived of the Liberty Loan plan. It had three elements. First, the public would be educated about bonds, the causes and objectives of the war, and the financial power of the country. McAdoo chose to call the securities "Liberty Bonds" as part of this educational effort. Second, the government would appeal to patriotism and ask everyone—from schoolchildren to millionaires—to do their part by reducing consumption and purchasing bonds. Third, the entire effort would rely upon volunteer labor, thereby avoiding the money market, brokerage commissions, or a paid sales force. The Federal Reserve Banks would coordinate and manage sales, while the bonds could be purchased at any bank that was a member of the Federal Reserve System.

To the war planners, the appeal of borrowing funds from the public was that it would be good for morale. Individuals could demonstrate their support for the war by purchasing bonds. Indeed, during the bond campaigns, purchasers were given buttons to wear and window stickers to display, thus advertising their patriotism. If bond sales were strong, if the offering was oversubscribed, that would demonstrate American resolve.

Yet there was a risk. Poor sales would be a sign of weak support and insufficient patriotism. To avoid a failure to sell the entire bond issue, the government arranged to sell them in a series of brief but intense campaigns by subscription. The first campaign was announced on April 28, 1917, twenty-two days after the declaration of war. The first offering of bonds was to be for $2 billion and promising a 3.5 percent rate of return. That was slightly below the rate paid by savings banks on customers' deposits (which ranged between 3.5 and 4 percent) or the yield on high-grade municipal bonds (3.9 to 4.2 percent). The fear was that individuals with preexisting savings accounts or municipal bond holdings would use those funds to purchase Liberty Bonds if the bonds' promised return was greater than what a savings account was earning. Such a rearrangement of portfolios would not have increased saving or reduced consumption. McAdoo also knew that financial institutions would resist mightily any competition for their deposits from the government.

The bonds were negotiable, with coupons cashable every six months. Although their term was thirty years, they were callable after fifteen. The lowest denomination available was $50.4 This, it seemed to some, would put them out of reach for the general public. The average compensation of a production worker in manufacturing was approximately 35 cents per hour at the time. Fifty dollars would require two weeks of wages. But there was an obstacle to issuing lower denominations: the government did not want to deal with the administrative cost of tracking ownership, so it designated Liberty Bonds as "bearer bonds." These are securities that belong to whoever is holding them at the time rather than one registered owner. Had bearer bonds been issued in small denominations, they could be used like currency to purchase goods, thereby defeating McAdoo's reason for refusing to print money. They would be money.

McAdoo found another way to make the bonds affordable. He introduced an installment plan. Even the poorest could purchase "War Thrift Stamps," which cost only 25 cents.5 The Treasury Department called them "little baby bonds," and like the Liberty Bonds, they earned interest. The stamps were pasted on a card until sixteen had been collected, at which point they were exchanged for a $5 stamp called a "War Savings Stamp." These were affixed to a "War-Savings Certificate" which also earned interest. When ten $5 stamps were collected, the certificate could be exchanged for a $50 Liberty Bond. The key to this scheme was that the certificate was registered to its owner and could be cashed only by the person whose name was inscribed on the certificate. That made the certificate non-negotiable.

Fears of inadequate demand were proved unwarranted. The first loan was oversubscribed by 50 percent, with more than four million subscribers accepted. Nationally, that would represent about one in every six households. Subscribers for the smallest amounts were given priority. Large subscribers were rationed. According to the New York Times, John D. Rockefeller, who pledged $15 million, was allotted only "something over $3 million." Fifty percent of the bonds sold were for the lowest face value, $50; another one-third of those sold were for the $100 bond.

In all, there were four Liberty Loan drives initiated during the war and a fifth "Victory Loan" announced after the armistice. The second Liberty Loan, for $3 billion, was open for six weeks and concluded on November 15, 1917. The third and fourth drives were each about a month long in April ($3 billion) and October ($6 billion) of 1918. Because interest rates on alternative assets had risen, the rates on the subsequent loans were increased to keep them competitive, to 4 percent on the second loan and 4.25 percent on the third and fourth. All five campaigns were oversubscribed. Purchasers of the first 3.5 percent bonds could exchange their securities for the new higher-yielding bonds.

The loan drives were the subject of the greatest advertising effort ever conducted. The first drive in May 1917 used 11,000 billboards and streetcar ads in 3,200 cities, all donated. During the second drive, 60,000 women were recruited to sell bonds. This volunteer army stationed women at factory gates to distribute seven million fliers on Liberty Day. The mail-order houses of Montgomery Ward and Sears-Roebuck mailed two million information sheets to farm women. "Enthusiastic" librarians inserted four-and-one-half million Liberty Loan reminder cards in public library books in 1,500 libraries. Celebrities were recruited. Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks, certainly among the most famous personalities in America, toured the country holding bond rallies attended by thousands.7

This elaborate effort was conducted by a home-grown propaganda ministry called the "Committee on Public Information." The propaganda campaign was essential, not just to sell bonds, but to sell the war. Public sentiment before 1917 was not only against American involvement in the war, but it was not even united on which European military to root for. Running for reelection in 1916, Wilson had adopted the campaign slogan "He kept us out of war," and he pushed his argument for noninvolvement relentlessly. Wilson's Republican opponent, Charles Evans Hughes, was also for peace. So, not surprisingly, his administration needed a major campaign to persuade the public of the necessity and the legitimacy of military action against Germany. This was a challenge because American involvement was not predicated on a desire for territory or revenge but on an intangible ideal. When asking for war on April 2, 1917, Wilson framed the war's objective: "The world must be made safe for democracy."

For the task of molding public opinion, Wilson turned to an investigative journalist, George Creel, who staffed the Committee on Public Information with psychologists, fellow journalists, artists, and advertising designers. The committee developed many of the techniques now associated with modern advertising. The magazine illustrator Howard Chandler Christy drew Liberty as an attractive young woman dressed in a see-through gown cheering on the troops. The man now regarded as the "father of public relations," Edward Bernays, also worked for Creel, pioneering the techniques of manipulating and managing public opinion based on the theories of mass psychology. The committee appealed to innate motives: the competitive (which city would buy the most bonds), the familial ("My daddy bought a bond. Did yours?"), guilt ("If you can't enlist, invest"), fear ("Keep German bombs out of your home"), revenge ("Swat the Brutes with Liberty Bonds"), social image ("Where is your Liberty Bond button?"), gregariousness ("Now! All together"), the impulse to follow the leader (President Wilson and Secretary McAdoo), herd instincts, maternal instincts, and—yes—sex. Bernays's uncle was Sigmund Freud.

By war's end, after four drives, twenty million individuals had bought bonds. That is pretty impressive given that there were only twenty-four million households at the time. More than $17 billion had been raised. In addition, the taxes collected amounted to $8.8 billion. Almost exactly two-thirds of the war funds came from bonds and one-third from taxes. This was a time when $17 billion was an almost unthinkably large number. An equal share of gross domestic product today would amount to $6.3 trillion. Most of McAdoo's bonds were purchased by the public, 62 percent of the value sold by one estimate. A government survey of almost 13,000 urban wage-earners conducted in 1918 and 1919 indicated that 68 percent owned Liberty Bonds. It seems undeniable that the emotional advertising campaign effectively produced a broad and strong desire to do one's part for the war effort by participating in this way. After the war, McAdoo's assistant in fiscal matters, Assistant Secretary Russell Leffingwell, described the loan campaigns "as the most magnificent economic achievement of any people. ... the actual achievement of 100,000,000 united people inspired by the finest and purest patriotism."

McAdoo had taken a gamble when he depended on faith that Americans could be induced to save more heavily than they would otherwise. He won that gamble. Saving rates shot up during the war and then returned close to their pre-war levels following the end of hostilities. Consumption as a percent of personal income fell during the war, by roughly 10 percentage points. McAdoo's faith in and reliance upon borrowing during a time of emergency proved the value of deficit spending and emboldened those who later advocated fiscal policy to fight business recessions and unemployment. McAdoo's belief that public opinion could be changed and mobilized to provide the will and the way to achieve great things provides a continuing foundation for an optimistic, progressive, and democratic view of our free-market capitalist economy.

Richard Sutch is the Edward A. Dickson Distinguished Professor of Economics (Emeritus) at the University of California, Riverside and Berkeley, and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Endnotes

- 1 The provision that the secretary of Treasury chair the Federal Reserve's Board of Governors was eliminated in 1936.

- 2 For details on this maneuvering, see the autobiographies of McAdoo [1931: 242-245] and Glass [1927: 101].

- 3 Accompanying the personal income tax was an increase in the corporate income tax, an entirely new "excess-profits tax," and excise taxes on such "luxuries" as automobiles, motorcycles, pleasure boats, musical instruments, talking machines, picture frames, jewelry, cameras, riding habits, playing cards, perfumes, cosmetics, silk stockings, proprietary medicines, candy, and chewing gum. These ad valorem taxes ranged from 3 percent on chewing gum and toilet soap to 100 percent on brass knuckles and double-edged dirk knives. A graduated estate tax on the transfer of wealth at death exempted the first $50,000 and rose progressively thereafter from 1 percent to 25 percent on amounts over $10,050,000. There were also a variety of miscellaneous war taxes introduced. These included taxes on transportation services; admissions to places of entertainment; social, athletic, and sporting club dues; a stamp tax on legal documents; a tax on the value of outstanding corporate stock; and a tax on the use of yachts.

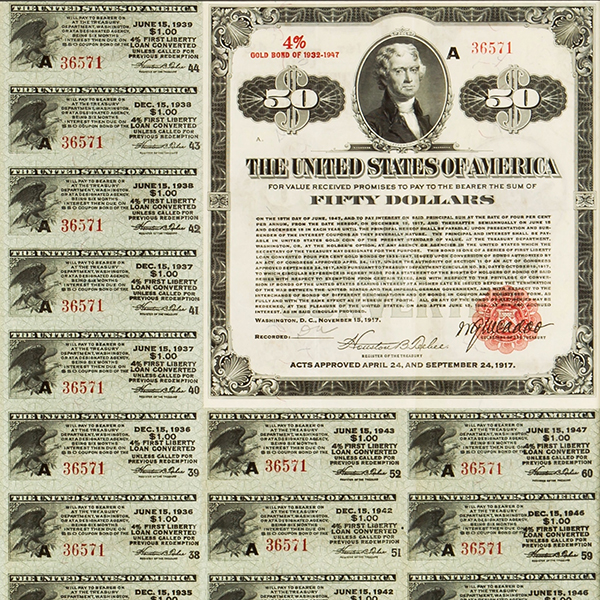

- 4 A Liberty Bond with its coupons. Twice each year the owner would clip out one of the coupons and cash it in at the local bank. This 4 percent bond sold for $50, and earned $1 every six months. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Joe I. Herbstman Memorial Collection of American Finance. Additional images of Liberty Bonds can be viewed at: http://www.theherbstmancollection.com/#!liberty-loans/c1cwm

- 5 A War Thrift Stamp. McAdoo felt that it was important to enroll children and women in the home front's war bond drives. Children were encourage to purchase these stamps and collect them in a booklet which might be exchanged for a Savings Certificate. Women were asked to take their change in thrift stamps when shopping. Note McAdoo's signature was reproduced on every stamp. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Joe I. Herbstman Memorial Collection of American Finance.

This article is drawn from:

Sutch, Richard, "Financing the Great War: A Class Tax for the Wealthy, Liberty Bonds for All," Berkeley Economic History Laboratory Working Paper WP2015-09, September 2015. Available online.

For firsthand accounts of the Liberty Bond Campaign and the collaboration between the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve see:

Glass, Carter. An Adventure in Constructive Finance: An Account of the Federal Reserve System. New York: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1927.

Leffingwell, R. C. "Treasury Methods of Financing the War in Relation to Inflation." Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science in the City of New York vol. 9, no. 1 (June 1920): pp. 16-41.

McAdoo, William G. "American Rights" [transcription of a sound recording], American Leaders Speak: Recordings from World War I and the 1920 Election, American Memory Project, Library of Congress, no publication date.

McAdoo, William G. Crowded Years: The Reminiscences of William G. McAdoo [with W. E. Woodward]. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1931.

United States Congress Joint Commission on Agricultural Inquiry. "Statement of Hon. Benjamin Strong, Governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York," in Agricultural Inquiry: Hearings, Before the Joint Commission of Agricultural Inquiry, Sixty-Seventh Congress, First Session Under Senate Concurrent Resolution 4 (August 2-5, 8-9 and 11, 1921).

Bibliography

Craig, Douglas B. Progressives at War: William G. McAdoo and Newton D. Baker, 1863-1941. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Staff. "Federal Reserve Act Signed by President Wilson: December 23, 1913." Federal Reserve History, last updated November 22, 2013.

Ghizoni, Sandra Kollen. "Reserve Banks Open for Business: November 1914." Federal Reserve History, last updated November 22, 2013.

Herbstman, Joshua T. "Joe I. Herbstman Memorial Collection of American Finance." Available online.

Mock, James R., and Cedric Larson. Words That Won the War: The Story of the Committee on Public Information, 1917-1919. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1939.

Schuffman, Lawrence D. "The Liberty Loan Bond." Financial History vol. 113 (Spring 2007): pp. 18-19.

Wheelock, David C. "The Fed's Formative Years: 1913-1929." Federal Reserve History, last updated November 22, 2013.

Written as of December 4, 2015. See disclaimer and update policy.

X

X  facebook

facebook

email

email