The Federal Reserve's Role During WWI

August 1914-November 1918

World War I was the first test of the new Federal Reserve System, and it was a trial by fire.

The outbreak of war in Europe in August 1914 touched off a financial crisis. The stock market closed and banks faced runs by depositors. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve Board and the twelve Reserve Banks were still getting organized. The crisis soon passed, but within months a new problem emerged. A large inflow of European gold to pay for US exports increased the money supply. The young Fed was powerless to offset the gold inflow or halt the resulting inflation. And once the nation entered the war, the Fed dedicated itself mainly to supporting the war effort.

But the conflict accelerated the evolution of the Federal Reserve into a true central bank by increasing its financial resources and transforming the US dollar into a major international currency. "The war reshaped the Federal Reserve System in many ways," writes economist Allan Meltzer in his landmark work A History of the Federal Reserve.

The Great War inflicted enormous human and economic costs on the combatants. Initially, Great Britain, France, and Russia allied against Germany and Austria-Hungary. For two and a half years the United States remained neutral, but in April 1917, Congress declared war on Germany. Still learning the ropes of a new system of monetary control, the Fed was called upon to help marshal the country's financial resources for war.

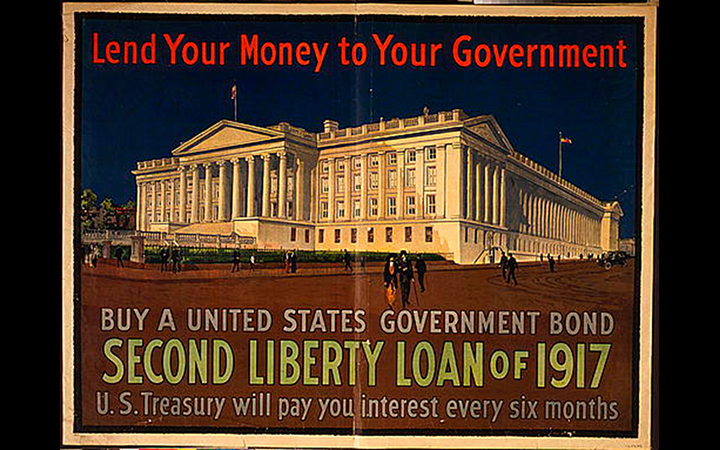

Federal spending surged as the military mobilized. Outlays for troop training, weapons, and munitions increased fifteen-fold from 1916 to 1918. In addition, the Treasury lent generously to US allies. Spending quickly outpaced tax revenues, and the Treasury mounted a series of war bond or "liberty loan" drives to raise additional funds.

The Federal Reserve took an active role in marketing war debt to commercial banks and the public. The New York Fed was designated the Treasury's fiscal agent for bond sales, and the governors of the Reserve Banks headed committees organized in each district to sell Treasury bonds.

Most important, the Fed leveraged its position as a lender to the banking system to facilitate war bond sales. To purchase war bonds over $1,000, the Treasury urged the public to "borrow and buy," that is, to finance their purchases at local banks. The Fed supported this policy by lending to member banks at low interest rates when the proceeds were used to buy bonds. Between bond drives, the Federal Reserve also lent at preferential rates to banks purchasing Treasury certificates—short-term borrowings issued in anticipation of tax receipts.

These fundraising efforts were very successful. By the spring of 1918, the federal government had sold roughly $10 billion ($155 billion in 2012 dollars) in war bonds and Treasury certificates.

As a result of Fed lending at low interest rates, credit conditions eased throughout the domestic economy, which was thriving on increased exports to Europe. Extensive borrowing by businesses and households stimulated economic growth but also increased the money supply, fueling inflation. In this period, raising or lowering interest rates on loans to member banks was the Federal Reserve's main tool for regulating credit and controlling inflation. Changes in the Federal Reserve "discount" rate in turn affected interest rates on commercial paper and other types of loans and securities.

However, Fed leaders did not take steps to raise interest rates to fight inflation. Congress created the Fed as an independent central bank to isolate it from political pressure, but during the war monetary policy was beholden to the needs of the Treasury. "Independence was sacrificed to maintain interest rates that lowered the Treasury's cost of debt finance," Meltzer (2003) writes.

The Fed Comes Into its Own

Although the Fed focused on war finance at the expense of inflation during World War I, it emerged as a major player on the world stage after the war as it developed into a full-fledged central bank.

The war resulted in larger Federal Reserve gold holdings as gold flowed from Europe to pay for munitions, food, and other US exports. Under the gold standard in force at the time, every dollar in the economy was at least partially backed by the precious metal. Some of the additional gold flowed into Federal Reserve Bank vaults as reserves, allowing the Fed to take on more assets in the form of government securities. A sizable portfolio of securities would become an increasingly important monetary tool after the war. Just as it does today, the Fed in the 1920s used purchases and sales of securities to influence market interest rates and implement monetary policy.

By wreaking financial havoc in Europe, the war also enhanced the standing of the U.S. dollar among the world's currencies. Huge military expenditures forced warring nations to abandon the gold standard; their money could no longer be redeemed for gold coin. But the dollar remained linked to gold. As the British pound and other European currencies became unstable, financiers and traders turned to the US dollar as a preferred medium of exchange.

The Fed's founders had wanted to foster the US dollar as a global currency by establishing a market for trade acceptances, bank drafts used to guarantee payment for imports or exports. The war created the conditions for such a market by making trade credit harder to obtain in Europe. To finance their operations, traders all over the world bought trade acceptances denominated in dollars, increasing both the international use of the dollar and business for American banks with overseas branches.

Victory by the United States and its allies ended the war in November 1918, ushering in a postwar boom as domestic demand rose and exports continued apace to supply war-ravaged Europe.

World War I was a watershed event that put the Federal Reserve System to a stern test. The war made the Federal Reserve subservient to the Treasury for a time. But it also helped the Fed develop the financial resources and expertise necessary to function as a central bank. After the war the Fed asserted its independence from the Treasury and took measures to bring down the inflation that threatened to stifle economic growth.

Top image: American Lithographic Co. poster from 1917, Library of Congress reproduction number LC-USZC4-8021

Bibliography

Broz, J. Lawrence. The International Origins of the Federal Reserve System. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997.

Eichengreen, Barry. Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Meltzer, Allan H. A History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 1: 1913-1951. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Weissman. Rudolph L. The New Federal Reserve System: The Board Assumes Control. New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1936.

Written as of November 22, 2013. See disclaimer and update policy.

X

X  facebook

facebook

email

email