Before the Fed: The Historical Precedents of the Federal Reserve System

1791-1913

Thomas Jefferson was proud of his home and architectural masterpiece, Monticello. So proud, in fact, that he placed a bust of himself in the foyer. He was also proud of his life in politics. To remind himself and visitors of his legacy, he placed a statue of his main rival, Alexander Hamilton, across the foyer.

Jefferson and Hamilton are archetypes of one of the most enduring debates in American politics, a debate over the nature of government and the centralization of political power. In many ways, the DNA of what would become the Federal Reserve System was a compromise between the two men's visions about the proper role of government in the economy.

Hamilton wanted the fledgling new country to grow and become a commercial and military rival to the great powers in Europe. In particular, he was impressed with the Bank of England, which had performed well as the central bank for a growing British Empire since it was established in 1694.

The California Institute of Technology historian John Brewer suggests that Britain's development from a peripheral player in Europe to one at the center of world affairs owed more to its bankers and bureaucrats than to its generals and soldiers. In his book The Sinews of Power, he wrote, "Victory in battle relied in the first instance upon an adequate supply of men and munitions, which, in turn, depended upon sufficient money and proper organization." Those commitments were met "thanks to a radical increase in taxation, the development of public deficit finance (a national debt) on an unprecedented scale, and the growth of sizable public administration devoted to organizing the fiscal and military activities of the state." 1

Even though the newly created United States of America was a fledgling nation, Hamilton saw its potential to rival the great powers of Europe. To achieve that, he developed a complex financial plan to help the country grow economically. The plan included establishing tariffs and other taxes for federal revenue, repaying the Revolutionary War debt acquired by the Continental Congress and all the states, chartering a national bank, and creating a national currency.

Jefferson, on the other hand, saw a different economic future for the new republic. He put more faith in an agriculture-based economy of yeoman farmers. He saw the benefits of large cities in terms of the culture and sophistication they engendered, but viewed them as fountains of corruption as well. He also considered industrial growth and the concentration of economic power in institutions such as banks as potential threats to liberty. Banks were particularly problematic for Jefferson since they encouraged speculation rather than making their money from honest labor, and he believed they tended to concentrate power in near monopolies.

These two worldviews collided over Hamilton's economic plans, which Congress adopted almost in their entirety. Those included the establishment of the Bank of the United States in 1791, which was granted a twenty-year charter. Jefferson opposed the Bank for many reasons, including his fear that it would primarily help the commercial North and concentrate wealth in cities. A bank chartered by the national government that could operate branches in all states would be an unfair competitor to state-chartered banks that operated in one place and received fewer federal advantages. Above all of these objections, however, Jefferson opposed the Bank because he did not think the Constitution gave Congress the power to create one.

The tensions between different visions of the proper role of government were made even more complicated by the competing interests of many different economic factions. For example, those who had capital wanted to see conservative monetary policy to safeguard against inflation, which would lower the value of their financial wealth. On the other side of the coin, those who needed capital to grow their businesses and farms tended to favor more liberal policies that eased access to credit, even at the risk of sparking inflation or a potential unstable banking system. The more established parts of the country—the wealthier cities of New England and the Mid-Atlantic, for example—often were in the former camp. Growing areas to the West and South were frequently in the latter. And each coalition had their political supporters.

These cross-cutting tensions about the role of government and different economic interests were always at odds in the efforts to manage the nation's finances, leading up to the creation of the Federal Reserve System. Negotiating among all those different interests would have been difficult during times of economic predictability and stable growth, but the nineteenth century was an era of great innovation, explosive growth, and radical changes to society. At the time of the first national bank—the first Bank of the United States—the nation was almost exclusively rural and agricultural. By the time of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, the country was industrializing rapidly and people were moving to cities in greater numbers. It is against this backdrop of extraordinary change and shifting battle lines among political factions, regional interest, and economic interests that this history must be understood.

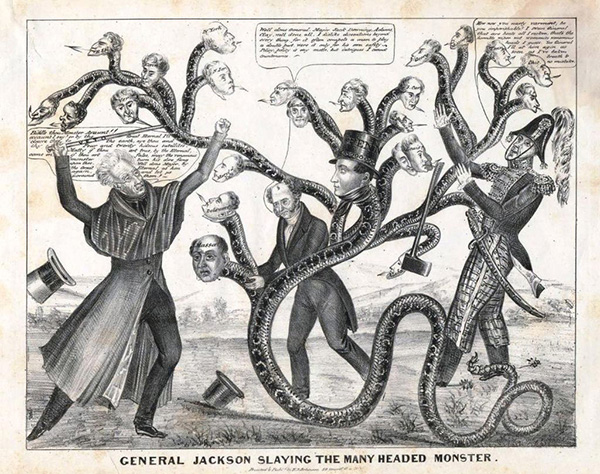

Second Bank of the United States, Andrew Jackson, and the Bank War

The first Bank of the United States had a twenty-year charter that expired just before the War of 1812. Disaster was barely averted in that war against Britain, thanks to a few key battlefield wins, but the inability of the federal government to wage war without a bank was made abundantly clear. When the war was going badly, even strong opponents of a central bank, such as Jefferson's political ally, President James Madison, reluctantly agreed to approve the creation of a second national Bank. Although Madison's enthusiasm waned when peace with the British seemed near, he ultimately signed the charter for the second Bank of the United States into law in April 1816; it opened for business in Philadelphia in 1817. In both structure and function, the second Bank was similar to the first Bank of the United States. It was a fiscal agent, holding federal deposits and issuing debt, and it engaged in bank supervision by issuing and redeeming bank notes that were deposited in state-chartered banks. It also operated as a commercial bank by accepting retail deposits and making loans to individuals and businesses through its twenty-five-bank network. Its early leadership had a mixed record, but that changed in 1823, when Nicholas Biddle took the reins. His sound management is credited with contributing to economic growth. Biddle soon found a foe in Andrew Jackson, who was a follower of the Jefferson line in his views on the role of government. He saw the Bank as too powerful, too insulated from congressional oversight, and too harmful to states' attempts to manage their local economies. In addition to Jackson's political objections, he also distrusted banks in general as dishonest players in the economy. Jackson's presidential adversary in 1832 was Sen. Henry Clay of Kentucky, who wanted to make an issue of Jackson's opposition. Clay thought he could rally support for the Bank—and by extension, his campaign—because the institution seemed to be working reasonably well. At his urging, the second Bank's charter came up for renewal ahead of schedule in 1832. It passed in the House and the Senate but then was stopped as Jackson vetoed it.

Jackson's attack on the Bank ultimately cast a long shadow in American history. While citing Jefferson's concerns about the Bank being an unconstitutional attack on state's rights, he managed a devastating political campaign in which he successfully portrayed the Bank as an elitist and "privileged" institution that benefitted the few. Because the Bank sold ownership shares through stock, Jackson argued, only the rich, both at home and abroad, benefitted from its operations. With this tactic, Jackson effectively portrayed the Bank as a tool of the special interests at the expense of "regular" people.

The Bank responded by lobbying for its preservation and inserting itself in the political process, but Jackson and his allies pointed to this as a sign of its corrupt practices. The Bank was much larger than the state-chartered commercial banks it competed against, so it had few friends in the banking sector.

Ahead of the end of the Bank's charter, Jackson moved its federal deposits out and distributed them in multiple state banks. Without federal funds, the Bank's operations shrank dramatically. It took another blow when its political defenders, the Whig Party, lost in the congressional elections of 1834. The Bank limped along after becoming a Pennsylvania state-chartered bank in 1836, but it closed its doors in 1841.

In the decades after Jackson's veto, the United States experimented with various institutional arrangements for regulating banks and currency, with rulemaking left largely to the states before the Civil War, followed by a period of nationally regulated banking in the decades after. Under these systems, the economy grew rapidly, but growth was interrupted by a series of financial panics during the Gilded Age, which culminated in the Panic of 1907.

A Progressive Response to a Radically Changing Society and Economy

We cannot fully understand the history of bank regulation and monetary policy without understanding the broader social, political, and economic contexts that were crucial to their development. During the time of the first Bank of the United States, for instance, about 5 percent of the US population lived in cities. At the time the Federal Reserve System was getting its start, the 1920 Census showed that more than half of Americans were urban.2 Similarly, in the early 1800s, most people's livelihood involved farming, and much of that was for their own consumption. By 1880, nearly 44 percent of the population lived on farms; by 1925, only 27 percent did.3 This enormous social change and the increasing complexity of the economy arguably exacerbated the consequences of the financial panics and other economic disruptions in later periods.

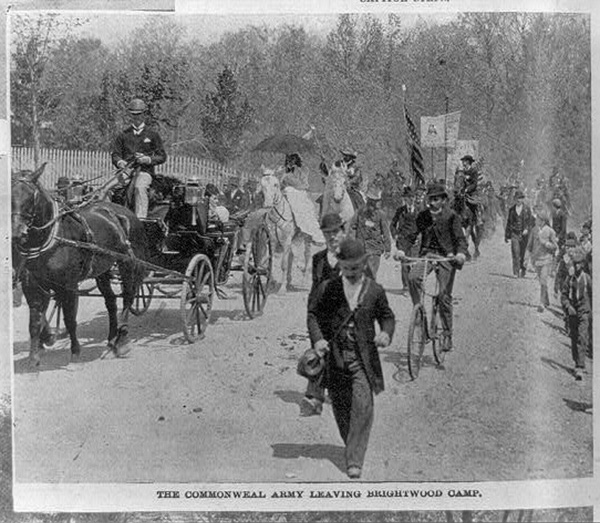

The Panic of 1893, for example, may have had similar drivers to earlier panics. But it occurred in a society that had so radically changed that the consequences of instability were amplified through an increasingly connected and industrialized national economy. The needs of unemployed workers stretched the limits of social networks that had historically provided economic support in hard times and a comprehensive safety net had not yet been established to provide public assistance. In 1894, unemployed laborers gathered to create "Coxey's Army" to organize a "March on Washington." The goal was to convince the federal government to do something to help put the unemployed back to work.

Demonstrations by the Occupy movement or anti-austerity protests in Athens are reminders today that periods of economic instability can have an emotional, and even violent, expression. So too was the situation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the United States. American society experienced substantial technological, demographic, social, and economic changes during that time. And the pressure was building to a point where conflict between capital and labor often escalated to violence in factory towns and mines across the country.

A constellation of reforms, often referred to as the Progressive Movement, attempted to keep old ideals intact while responding to new realities that were tearing the fabric of the nation. Richard Abrams, a historian at the University of California, Berkeley, writes that the Progressives "sought a peaceful, legal substitute for Gatling guns and bayonets." In full force from the late 1880s until the early 1920s, the movement comprised a variety of groups and factions, including those who wanted to reform the civil service, "female emancipationists, prohibitionists, the social gospel, the settlement-house movement, some national expansionists, some world peace advocates, conservation advocates, technical efficiency experts, and ... intellectuals," in Abrams' words. The Progressive Movement had many inspirations and competing goals, but at its core was an effort to create "a more morally perfect society," according to Abrams.4 There were limits to this vision, though, as the Progressives generally tolerated, and in some cases promoted, racial segregation. "Most of the progressives told themselves that separation allowed reform to continue," writes Indiana University historian Michael McGerr. "Protected by the shield of segregation, the fundamental project of transforming people could go in safety. But the cost was great."5

Progressives wanted to reform all levels of government—municipal, state, and federal. In many places, it started as a local effort to wrest control of city government from the political bosses, but it also had larger aims to use science and efficiency to make government work better.

Toward a Progressive Banking Policy: The National Monetary Commission Study, Aldrich Plan, and the Federal Reserve Act of 1913

Progressive Movement thinking was front and center when reformers looked to improve the nation's chaotic banking system, especially after it failed to respond to the Panic of 1907, which took place in an already weakened economy. It would have been much worse had it not been for the intervention of finance titan J.P. Morgan. Even with Morgan's efforts, the financial contagion spread through the country and left many broken banks in its wake. As Jon Moen and Ellis Tallman write on this site, the Panic of 1907 and the 2008-09 financial crisis both started among New York City financial institutions and markets, and like the recent crisis, the effects of 1907 were felt throughout the nation and the rest of the world.

The crisis and the paucity of tools available to respond to it triggered a substantial review of our financial system. In 1908, Congress passed the Aldrich-Vreeland Act to establish the National Monetary Commission. The commission's charge was to assess the recent panic and provide a systematic analysis of currency and banking reform. Sen. Nelson Aldrich, a Rhode Island Republican and leading reformer, described the panel's mission in a speech before the Economic Club of New York in 1909. "I believe if it should be thought wise by the commission, supported by the consensus of intelligent opinion of the people of the United States, to adopt any system, that neither the political prejudice of the past nor the ghost of Andrew Jackson, that great man who died many years ago, will stand in the way," he said.6 Not only would the country move beyond the ghosts of its past, added Aldrich, it would use science and efficiency to create a modern banking system that would benefit "people of every class and every section."

The commission's report concluded that the new central bank would have functions felt equally by "wage earners, farmers, manufacturers, and all others engaged in productive industry."7 In other words, the new banking system would use good governance, best practices, and scientific methods to create an institution to help heal the many rifts that have been present from the beginning of the republic. (For more on the National Monetary Commission, see the essay on "The Meeting at Jekyll Island" on this site.)

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 was the result of those efforts. In many ways, it was a compromise solution of the Aldrich Plan that came out of the National Monetary Commission, pulling together many different traditions. During its first century, the Federal Reserve System would continue to evolve in its form and function, but its ability to strike many compromises—to be a "decentralized central bank"—was a hallmark to its endurance as an institution in American life.

Endnotes

- 1 John Brewer, The Sinews of Power: War, Money, and the English State, 1688-1783, xv and xvii.

- 2 https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/1990/tables/cph-2/table-4.pdf

- 3 https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/historical-statistics-united-states-237

- 4 Richard Abrams, "The Failure of Progressivism," in The Shaping of Twentieth Century American: Interpretive Essays, 210

- 5 Michael McGerr, A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870-1920, 183-184

- 6 An Address By Senator Nelson W. Aldrich Before the Economic Club of New York, November 29, 1909, on the Work of the National Monetary Commission, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/610.

- 7 The Report of the National Monetary Commission, January 9, 1912, p. 40. Available at: https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/report-national-monetary-commission-4958.

Bibliography

Abrams, Richard M., "The Failure of Progressivism," in The Shaping of Twentieth Century America: Interpretive Essays. ed., Richard M. Abrams and Lawrence W. Levine, Boston: Little, Brown, 1965.

Aldrich, Nelson W. "The Work of the National Monetary Commission," An Address By Senator Nelson W. Aldrich Before the Economic Club of New York, November 29, 1909. Available on FRASER.

Brewer, John. The Sinews of Power: War, Money, and the English State, 1688-1783. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988.

McGerr, Michael. A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement, 1870-1920. New York: Free Press, 2003.

National Monetary Commission. Report of the National Monetary Commission, January 8, 1912. Available on FRASER.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Bicentennial Edition, Parts 1 and 2. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1975. Available on FRASER.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. "Population: 1790 to 1990." Population and Housing Unit Counts Table 4, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/1990/tables/cph-2/table-4.pdf, accessed October 16, 2015.

Written as of December 4, 2015. See disclaimer and update policy.

X

X  facebook

facebook

email

email